#3 in series by Matthew Liotine, Ph.D. , Strategic Advisor, Business Intelligence and Operations, Professor University of Illinois

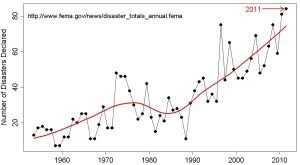

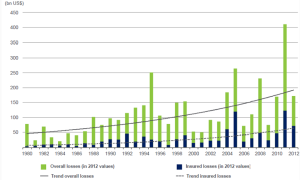

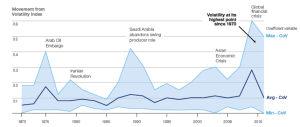

In our previous articles, we discussed how disruptions to a supply chain can originate from a multitude of sources. According to some current trends, it is apparent that there is continued rise in measured losses from disruptions such as natural events and business volatility. Traditionally, supply chains are designed for lean operational efficiency wherever possible, yet such efficiency requires the minimization of excess capacity, inventory and redundancy – the very things that are needed to create resiliency against disruptive risks. Risk assessment tools and methodologies help decision-makers to identify the most cost effective controls that can strike the right balance between cost and risk reduction to protect against disruption. Typically, the most cost effective controls are those that can minimize the common effects arising from multiple disruptive threats. In order to understand the kind of controls that could be effective, one must recognize the risk outcomes from common supply chain vulnerabilities, which is the focus of this article.

What is Risk?

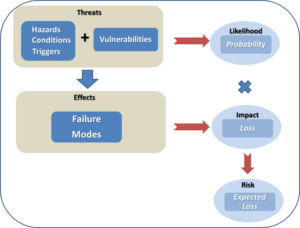

Before continuing, it would be worthwhile to revisit some of the terminology that we have been using in previous discussion, in order to understand how risk is derived. Fundamentally, risk is the chance (or the probability) of a loss or unwanted negative consequence. For decision purposes, it is often calculated numerically as a function of probability and impact (sometimes called single loss expectancy), and quantitatively expressed as an “expected” loss in monetary value or some other units. A common flaw with using risk values is that they mask the effects of impact versus probability. For example, an expected loss of $100 does not reflect whether high impact is overwhelming low probability, or high probability is overwhelming low impact. Thus, it is not clear whether this value is the expected loss due to an event that occurs 10% of the time and causes $1000 in damages when it occurs, or due to an event that occurs 20% of the time and causes $500 in damages when it occurs. For this very reason, risk values must be used in conjunction with probability and damage values, along with many other metrics, in order for the decision maker to compare the one risk against another. Risk values are not precise and are usually not to be used as standardized values for business management. Nevertheless, risk values can be used to provide decision makers with a means to distinguish risks and control options on a relative basis. Figure 1 illustrates the fundamental parameters that are used to construct risk values, and how they relate to each other.

Figure 1 – Fundamental Components of Risk

Hazards, conditions and triggers are situations that increase or cause the likelihood of an adverse event (sometimes referred to as a peril). In our last article, we examined numerous sources of hazards that can threaten a supply chain. Vulnerabilities are factors that can make a system, in our case a supply chain, susceptible to hazards. They are usually weaknesses that can be compromised by a hazardous condition, resulting in a threat. The likelihood, or probability, of a threat circumstance occurring must be considered, for reasons discussed above. If it occurs, failures can take place, whose effects are quantified as impacts. When impacts are weighed against the likelihood of the threat, the result is a risk that poses an expected loss. Controls are countermeasures that a firm can use to offset expected losses.

With respect to a supply chain, there are many ways to classify risk. Academics have made many attempts to try to classify risks according to some kind of ontology or framework (Harland, Brenchley and Walker 2003) (Gupta, Kumar Sahu and Khandelwal 2014) (Tummala and Schoenherr 2011) (Peck 2005) (Monroe, Teets and Martin 2012) (Chopra and Sodhi 2004). Some of the more common supply chain risk classifications include:

Recurring risks – These risks arise within the operational environment due to the inability to match supply and demand on a routine basis. The ensuing effects are lower service levels and fill rates.

Disruptive risk – These risks result from loss of supply or supplier capacity, typically driven by some disruptive event.

Exogenous risk – These risks arise within the operational environment and are process driven (e.g. poor quality control, design flaws, etc.), usually within the direct influence of the firm. They typically require the use of preventive mechanisms for control.

Endogenous risk – These risks originate externally, either from the supply side or demand side, which may not necessarily be under a firm’s direct influence. They typically involve the use of responsive mechanisms for control.

While many classification attempts have been noble in nature, in the end it is difficult to classify risks according to a single scheme, for a variety of reasons. First, the lines of demarcation between risk categories can be blurred and there could be overlap between them. For example, from the above categories, one can easily argue about the differences between exogenous and recurring risks. Second, every firm is different, and thus one framework may not fit all. Finally, risk methodology approaches may differ somewhat across various industries, as evidenced by different industry best practices and standards for risk analysis.

Supply chains can exhibit many kinds of vulnerabilities, but quite often these can be viewed as either structural or procedural in nature. Structural vulnerabilities stem from deficiencies in how the supply chain is organized, provisioned and engineered. Single points of failure can arise when there is insufficient diversity across suppliers, product sources or the geographical locations of sources. Inadequate provisioning can create shortages in inventory or capacity to meet customer demands. Procedural vulnerabilities stem from deficiencies in business or operational processes. Gaps and oversights in planning, production or transport processes could adversely affect a firm’s ability to respond to customer needs. Insufficient supply chain visibility could render a firm blind to oversights in supplier vetting and management practices, quality assurance and control, or demand planning.

Such kinds of vulnerabilities, combined with an aforementioned hazardous condition, results in the supply chain failing in some fashion. Table 1 illustrates some of the more common modes of supply chain failure.

Table 1 – Common Supply Chain Failure Modes

| Degraded fill rate

Degraded service level High variability of consumption Higher product cost Inaccurate forecasts Inaccurate order quantity Information distortion Insufficient order quantities |

Longer lead times/delays

Loss of efficiency Lower process yields Operational disruption Order fulfillment errors Overstocking/understocking Poor quality supplied Supplier stock out |

Ultimately, such supply chain failures result in increased costs, loss of revenue, loss of assets, or combination thereof. Common risks are typically assessed as increases in ordering costs, product costs, or safety stock costs. Product stock out losses can be assessed as backorder costs or loss of sales and business revenue. Different kinds of firms will be prone to different types of risks. For example, a manufacturing firm with long supply chains will be more susceptible to ordering variability (or bullwhip) types of effects versus a shorter retail supply chain which would be more sensitive to fill rate and service level variability. Understanding and characterizing these risks is necessary in order to develop strategies to control or manage them. Quantifying risks provides the decision maker with a gauge to assess risk before and after a control is applied, thereby assessing the prospective benefit of a potential control. Using quantified risk values, in combination with other parameters, enables a decision maker to prioritize potential control strategies according to their cost-effectiveness.

Conclusions

Risk is the chance or the probability of a loss or unwanted negative consequence. Inherent supply chain weaknesses such as sole sourcing, process gaps or lack of geographical sourcing diversity can render a supply chain more vulnerable to some hazardous, unforeseen condition or trigger event, such as a strike or major storm, resulting in undesirable increases in costs, asset loss or revenue loss. Such risks can be quantified to some extent, quite often in monetary units, and can be used to facilitate cost-benefit analysis of potential control strategies. In our next article, we will take a look some of the most favored strategies to control supply chain risk.

Bibliography

Chopra, S., and M. Sodhi. “Managing Risk to Avoid Supply-Chain Breakdown.” MIT Sloan Management Review, 2004: 53-61.

Gupta, G., V. Kumar Sahu, and A. K. Khandelwal. “Risks in Supply Chain Management and its Mitigation.” IOSR Journal of Engineering, 2014: 42-50.

Harland, C., R. Brenchley, and H. Walker. “Risk in Supply Networks.” Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management, 2003: 51-62.

Monroe, R. W., J. M. Teets, and P. R. Martin. “A Taxonomy for Categorizing Supply Chain Events: Strategies for Addressing Supply Chain Disruptions.” SEDSI 2012 Annual Meeting Conference Proceedings. Southeast Decision Sciences Institute, 2012.

Peck, H. “Drivers of Supply Chain Vulnerability.” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 2005: 210-232.

Tummala, R., and T. Schoenherr. “Assessing and Managing Risks Using the Supply Chain Risk Management Process (SCRMP).” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 2011: 474-483.